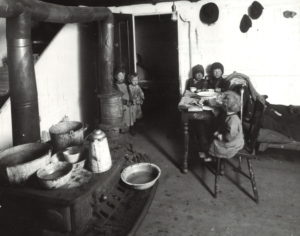

The need for public housing in Winnipeg can be traced back as far as the 1880s. By then, Winnipeg had identifiable “shanty towns” located near the rail lines and east of Main Street on what was termed the ‘Hudson’s Bay Flats.’ The Winnipeg Daily Sun reported in 1883 that one shantytown was made up of “not less than three hundred little wooden shanties, varying in size from that of a large dog-house to a good-sized ash-house.” (An ash house was a small shed for the storage of ashes, which were used to make soap.) The shanties cost between $50 and $115 to build and were occupied by an estimated two thousand people who could not afford the local “high rents.”[1] Shanties twelve by sixteen feet in size were advertised for sale in local papers. The shanties, which were often located on the public roadways, were fire hazards, so flimsy that a strong wind could pick them up and blow them away.[2]

From then on there was a portion of the city’s populace that could not afford to rent housing that was safe and healthy. Safe and healthy simply means housing that was warm enough, sturdy enough, properly ventilated, free from fire hazards, provided with adequate plumbing, and allowed for a modicum of privacy. A considerable portion of Winnipeg housing failed to meet these criteria when judged by the common standards of the day.

What, then did families that could not afford to rent adequate housing do? They generally had two options: they cut down on what they spent on food and clothing and paid rents that they could not afford, or they crammed more people than were healthy into adequate housing. Or they did all these things and still ended up living in substandard housing.

For each of these families getting and maintaining housing was a crisis that dominated their lives. Could they find a house, would they be evicted if a wage earner was injured, were conditions so crowded that typhus or diphtheria would rip through the tenement living a trail of sick and dying children, on a night when the temperature hit forty below would a spark from a cheap stove set the whole building a light, would anyone ever enjoy a moment’s privacy? But it is not possible to say Winnipeg itself had a housing ‘crisis’ since that would imply that the shortage of good quality affordable housing was a rupture, a break from some normal condition in which modestly priced healthy housing was available for all. There was no golden age: the constant crisis of individual low-income households faced in the search for housing has been continuous throughout Winnipeg’s history. It is possible to find reports from each decade of the first century of the city’s history that speak in sober, matter-of-fact tones of the extent of inadequate housing and the city’s inability to enforce its housing and health bylaws, since to do so would be to force families on the street.

In the fall of 1903, the Manitoba Free Press published a letter to the editor from “One who pays rent,” that laid bare the problems that working-class families faced when looking for a place to live in Winnipeg. In an age when a non-skilled labourer made less than five hundred dollars a year, there were “Three-roomed suites with bath attached are renting for $35, and it is not unusual for applications to be 20 or 30 deep for any possible vacancy in such blocks. More than this there are suites of two rooms without outside light or ventilation that bring in $18 a month to the landlord.[3]

It was not until 1909 that the city adopted a tenement bylaw. In a detailed critique of the bylaw’s failings, local architect William Bruce observed that the bylaw was “certainly no improvement on present conditions, except to give a sort of legal status to badly lighted, deficiently ventilated and overcrowded erections, where friendly interests are at stake.” The best clauses in the bylaw, he wrote, were dead for lack of enforcement.[4]

In January 1914 the Free Press reported that city housing officials were exercising leniency in enforcing the housing bylaws since it was apparent the tenants had no place to go.[5] The city’s sanitary inspection report of 1928 stated, “We see little, if any change in the condition of a large number of one-family dwellings now occupied unlawfully as tenements.” For the city as a whole, the number of infant deaths to 1,000 live births was nine. However, in the four sections of the city that bordered the Canadian Pacific Railway yards, the rate was 33 per 1,000.[6]

In his 1938 annual survey of housing the city’s chief housing office, Alexander Officer, wrote:

There is little I can say that has not been said previously. I have been pointing out for years the deficiency in housing accommodation for our low-wage earners; that bad housing is unprofitable to the community; that our substandard housing is increasing in area and even invading some of our better class residential districts; and that we are finding more and more single family dwellings occupied as tenements, many families have only one room.

According to Officer, “The serious shortage of dwellings for the low-wage earning class become more acute every year.”[7] There was, he estimated, a need for 5,000 new housing units in Greater Winnipeg.[8] Two years later he wrote, “Slum conditions are rapidly developing in this city, becoming more acute in certain sections and beginning to show evidence in districts that only a few years ago were considered exclusive.”[9]

In the spring of 1941, Winnipeg was reportedly experiencing the most serious housing crisis in the city’s history. Officials estimated that enforcement of the city’s public health laws would likely have led to the eviction of at least 6,000 families.[10] Dr. Morley Lougheed, the city’s medical health officer, called local housing conditions disgraceful, adding “We could fill the paper with incidents of families living under conditions which are against the law.”[11]

In 1949 city Emergency Housing official William Courage reported “thousands of low-income workers are ill-housed in over-crowded, sub-standard dwellings in congested areas.” The strict enforcement of building and health bylaws would result in further hardship as people would be evicted with a “lack of alternative accommodation.”[12] The city’s medical health officer Morley Lougheed said the housing situation was worse than it had been at the end of the war.[13] And in 1953, Frank Wagner, the chair of the city’s housing committee described city housing conditions as being “worse than ever.”[14] At least once a month in the late 1950s tenants would refuse to vacate rented premises that the city had declared unfit for habitation because they had nowhere else to go. The tenants were usually welfare recipients and the city found itself forced to continue to pay rent to the landlord.[15]

In the spring of 1967 Toronto consultant James A. Murray, who had been commissioned by the Metropolitan Corporation to survey housing conditions in Greater Winnipeg, pointed out that the local housing industry was focused on meeting the housing needs of approximately fifty per cent of the population. The other fifty per cent of the population was either living in housing that was overcrowded or substandard or more than they could afford—or all three. 35,000 families needed some form of housing subsidy—and there were only 2,000 housing units that met their needs. Seniors were particularly hard hit, 43 per cent of the single people were living on less than $1,500 a year, the figure that the Age and Opportunity Bureau had concluded in 1966 that a person needed to live independently on their own.[16]

These conditions continue into the second decade of the twenty-first century. Writing in 2022, it is possible to say that in each year of the past decade, the Winnipeg Free Press has carried stories that speak of the ongoing affordable housing “crisis” in the city.[17]

The implications of the historic, continuing failure of the private housing market are straightforward. It cannot be counted on to provide affordable housing to low-income people. The solution is some form of public housing. This was clear in as early as 1908.

Back to The Struggle for Affordable Housing in Winnipeg

[1] “Among the shanties,” Winnipeg Daily Sun, January 31, 1883.

[2] “City and province,” Manitoba Daily Free Press, November 8, 1883. “A phenomenon,” Manitoba Daily Free Press, May 22, 1885; W.O. McRobie, “Of the doings of the fire brigade the past year,” Winnipeg Daily Sun, December 27, 1884. “For sale,” Winnipeg Daily Sun, January 14, 1884.

[3] One who pays rent, “Rents in Winnipeg,” Manitoba Free Press, November 30, 1903. For income information, see: Alan F.J. Artibise, Winnipeg: A social history of urban growth, 1874–1914, Montreal: McGill-Queen’s, 1975, 226–240.

[4] William Bruce, “Building bylaws of Winnipeg,” Winnipeg Tribune, November 5, 1909.

[5] “Campaign for better housing,” Manitoba Free Press, January 5, 1914.

[6] “Winnipeg’s war for health,” Manitoba Free Press, July 5, 1928.

[7] “Acute shortage of houses for low-wage class,” Winnipeg Free Press, January 27, 1938.

[8] “Expert says 5,000 new houses needed in Greater Winnipeg,” Winnipeg Free Press, February 12, 1938.

[9] “Housing in Winnipeg,” Winnipeg Free Press, January 23, 1940.

[10] Dick Sanburn, “400 facing moving day without homes,” Winnipeg Tribune, April 23, 1941.

[11] “Moving day brings new housing jam,” Winnipeg Tribune, April 30, 1943.

[12] 4,234 apply for housing; 320 placed,” Winnipeg Free Press, January 14, 1950.

[13] “54 live in city cellars; housing problem worse,” Winnipeg Tribune, January 28, 1950.

[14] “Council okays plan for low-rent homes,” Winnipeg Free Press, August 5, 1953.

[15] “Won’t pay rent for unfit houses,” Winnipeg Tribune, December 8, 1959.

[16] Wade Rowland, “Housing report to cause political storm,” Winnipeg Free Press, March 14, 1967.

[17] Mary Agnes Welch, “Rooming-house loss a crisis,” Winnipeg Free Press, July 12, 2013; Mary Agnes Welch, “People before parks,” Winnipeg Free Press, June 15, 2014; Mary Agnes Welch, “Group touts cure to affordable housing woes,” Winnipeg Free Press, June 23, 2015; Christina Hryniuk, “Housing can be harrowing,” Winnipeg Free Press, November 27, 2016; Kirsten Bernas, “Falling behind on homelessness,” Winnipeg Free Press, October 25, 2017; Dylan Robertson, “Budget fails to speed up funding,” Winnipeg Free Press, February 28, 2018; Tessa Vanderhart, “Lockers to rescue city homeless and their carts,” Winnipeg Free Press, June 22, 2019; Joyanne Pursaga, “City report considers supports to address homelessness,” Winnipeg Free Press, September 15, 2020; Joyanne Pursaga, “City keeps tax hike plans intact,” Winnipeg Free Press, November 26, 2021; Ben Waldman, “A hand up in St. B,” Winnipeg Free Press, January 24, 2022.