The biggest funder of public housing in Canada has been the federal government. But for the first half of the twentieth century, the federal government argued that housing was a provincial responsibility. While the federal government did introduce a loan program to assist homeowners after the First World War and to build housing for war-industry workers and returned veterans after the Second World War, it always characterized these as temporary, emergency programs.

It was not until 1949 that the federal government changed course, passing amendments to the National Housing Act that committed it to providing seventy-five per cent of capital funding for low-income projects whenever a provincial government arranged the remaining twenty-five per cent. The federal government was also prepared to cost-share operating losses on a similar basis, a provision that would allow for the subsidization of rents.

At the time skeptics feared that provincial government disinterest in public housing would prove to be a near insurmountable barrier to the development of low-cost housing. They were correct: across Canada, only 11,000 units of low-cost housing were created over the next fourteen years.[1] In Manitoba, not a single unit of housing was funded under these provisions from 1949 to 1962.

Douglas Campbell, a farmer who had first been elected in the Manitoba legislature in 1921, was premier from 1948 to 1958. His Liberal government ignored the concerns of urban voters, who were dramatically under-represented in the legislature. In 1952 Manitoba had 228,280 urban voters and 224,083 rural voters, but urban areas had only seventeen seats in the legislature compared to forty rural seats.[2] The Campbell government was also notoriously tight-fisted. Earl Levin, who served in various city planning capacities in Winnipeg in the 1960s, described the Campbell administration as a “do-nothing government, paralyzed by its obsession with government economy and holding down taxes.”[3]

Civic officials from Winnipeg, Brandon, St. Boniface, East and West Kildonan, Selkirk, Transcona, and Brooklands, along with representatives of the National Council of Women, the Canadian Legion, the Council of Social Agencies, the Community Planning Association, the One Big Union, the Federation of Civic Employees, and the Winnipeg and District Labour Council all lobbied the Campbell government to take advantage of the federal government funding available through the NHA.[4]

In the end, all the province was prepared to do was pass a Manitoba Housing Act that gave the province the right to enter into a housing agreement with the federal government but did not commit it to spending money on either the construction or operation of public housing.[5] The Manitoba Housing Act also prohibited municipalities from borrowing to fund a housing project under the NHA unless the borrowing had been approved by sixty per cent of the voters in ratepayers’ vote.[6] Only property owners could vote in such a referendum.[7] As St. Boniface mayor George MacLean said, rather than enabling its construction, the Manitoba Housing Act was “killing low-rent housing.”[8]

In 1958, Duff Roblin led the Progressive Conservative Party to victory in that provincial year’s election. Roblin succeeded by moving the Conservatives to the political centre, presenting them as the party of modernity and progress. While housing was not a government priority, unlike his predecessor, Roblin was prepared to work with the city to address urban problems.[9] In February 1959, just six months after being elected premier, Roblin proposed to Mayor Stephen Juba that a three-person committee be established with a mandate to survey urban redevelopment in the city. Roblin told the Free Press, “I saw the centre of the city rotting and I thought I should do something about it.”[10] One of the most important things it did was eliminate the requirement for a ratepayers’ vote on housing public-housing projects in Winnipeg.[11] Despite its commitment, the Roblin government was guilty of foot-dragging: at a key point, it held off on making a financial commitment to the acquisition of land for the construction of new housing until a survey of provincial needs was completed.[12] It also continued to require municipalities to match the provincial contribution to

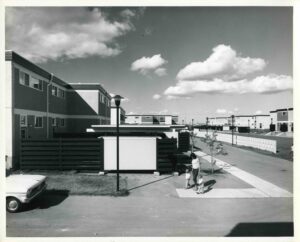

While the Conservatives held power from 1958 to 1969, only two public-housing projects, Burrows-Keewatin (now known as Gilbert Park) and Lord Selkirk Park projects, were developed in the entire province.

The New Democratic Party’s surprise victory in the June 1969 Manitoba provincial election marked a historic turning point in the history of public housing in Manitoba. NDP premier Ed Schreyer and his government stopped asking municipalities to cover any portion of capital and operating costs. In 1970 the government committed itself to building between 900 and 1,000 units of public housing in the coming year, almost double what had been built in the previous decade. In the financial year of 1970-71, 2,409 units of public housing were put into construction. The scale of increase in the investment in construction is staggering: $3,273 in 1969, $848,371 in 1970, $7,583,939 in 1971, and $31,499,744 in 1972.[13] Several of the projects were innovative for their time: 1010 Sinclair was the first public housing project for people living in wheelchairs while the Kiwanis Centre for the Deaf was also a new step in housing for people with disabilities.[14]

At the end of the eight-year Schreyer administration, there were 11,187 units of public housing in the province.[15] In his 1980 assessment of Canadian housing policy, Canadian public housing scholar Albert Rose commented that “Manitoba’s record in a variety of housing assistance programs, with particular emphasis upon public housing, is all the more impressive when its population of just over 1 million persons is considered.”[16]

Back to The Struggle for Affordable Housing in Winnipeg

[1] John Bacher, Keeping to the Market: The Evolution of Canadian Housing Policy, Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993, 183.

[2] Christopher Adams, Politics in Manitoba: Parties, leaders and voters, Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2008, 36, 80, 111; Christopher Adams, “Realigning elections in Manitoba,” in Manitoba politics and government: Issues, institutions, traditions, edited by Paul Thomas and Curtis Brown, Winnipeg: University of Manitoba, 2010, 176; James Muir “Douglas L. Campbell, 1948–1958” in Manitoba premiers of the 19th and 20th centuries, edited by Barry Ferguson and Robert Wardhaugh, Regina: Canadian Plains Research Centre, 2010, 228.

[3] Paul Barber, “Manitoba’s Liberals: Sliding into third,” in Manitoba politics and government: Issues, institutions, traditions, edited by Paul Thomas and Curtis Brown, Winnipeg: University of Manitoba, 2010, 136; Earl Levin, “City History and City Planning: The Local Historical Roots of the City Planning Function in Three Cities of the Canadian Prairies,” Ph.D. thesis, University of Manitoba, 1993, 257.

[4] “Housing head says Manitoba still may help,” Winnipeg Free Press, March 27, 1950;“City groups to press for low-rent housing,” Winnipeg Tribune, January 31, 1950; “Join housing plea, urban groups asked,” Winnipeg Tribune, February 22, 1950.

[5] “City Council Seeks Housing Authority,” Winnipeg Tribune, 2 May 1950; “Legislature to get low-cost housing bill,” Winnipeg Free Press, March 14, 1950.

[6] “Housing aid bill wins 2nd reading,” Winnipeg Tribune, April 20, 1950.

[7] “Motion Would Give All Voters A Voice In Money Decisions,” Winnipeg Free Press, 20 September 1949.

[8] “Province ‘kills’ low rent housing, MacLean charges,” Winnipeg Tribune, March 25, 1950; “Suburbs rap province for ‘killing’ housing,” Winnipeg Free Press, March 24, 1950.

[9] Cy Gonick, “The Manitoba economy since World War II,” in The Political Economy of Manitoba, edited by James Silver and Jeremy Hull, Regina: Canadian Plains Research Centre, 1990.

[10] “Duff wants to get down to business” and “He sees our city decaying,” Winnipeg Free Press, February 6, 1959.

[11] “Move to bypass ratepayer,” Winnipeg Free Press, December 29, 1959; Ted Byfield, “Last interview recalls lifetime of fighting,” Winnipeg Free Press, April 13, 1968.

[12] “Province slum aid is delayed,” Winnipeg Tribune, March 21, 1961.

[13] Manitoba Housing and Renewal Corporation, Annual Report 1968–69, Winnipeg: Manitoba Housing and Renewal Corporation, n.d.; Manitoba Housing and Renewal Corporation, Annual Report 1969–70, Winnipeg: Manitoba Housing and Renewal Corporation, n.d.; Manitoba Housing and Renewal Corporation, Annual Report 1970–71, Winnipeg: Manitoba Housing and Renewal Corporation, n.d; Manitoba Housing and Renewal Corporation, Annual Report 1971–72, Winnipeg: Manitoba Housing and Renewal Corporation, n.d.; Manitoba Housing and Renewal Corporation, Annual Report 1972–73, Winnipeg: Manitoba Housing and Renewal Corporation, n.d.; Manitoba Housing and Renewal Corporation, Annual Report 1973–74, Winnipeg: Manitoba Housing and Renewal Corporation, n.d.

[14] Albert Rose, Canadian Housing Policies (1935–1980), Toronto: Butterworths, 1980, 87.

[15] Manitoba, Manitoba Housing and Renewal Corporation, 1977–78 Annual Report, Winnipeg: Manitoba Government, 1978.

[16] Albert Rose, Canadian Housing Policies (1935–1980), Toronto: Butterworths, 1980, 87.